Persecution saturates the neck of young women. This damp exterior, crushed between jagged ribs and the unbecoming ill-remains of fat, will become explicit, R-rated, subverted to a perversion of this body, her body. Forget about the care we show intent — it is now stretched, disjointed; an awkward veil of femininty (lace and all.)

[I could be remarkable, and prudish.]

Should I talk upon the juvenile nature of flexibility? Where, the extension of ones hips [the landscape for childbirth] & career & jaw, remains sexual. Deceptiveley delicate ‘the woman’ is.

Either way, the post / pre / birth of modern misogyny aligns a women to be knowledgeable in its ‘devices’ — that which shocks, suffocates, pricks, invades, redefines. That of a collar or hand, of personal persuasion to bind the stomach, the fat under the arms, the placement of the toes upon the feet — how they should curve until the bones snap.

Then, there is the awful codification of ‘muse’, which could have been disastrous, but remained ill-defined as women began to carve space into art and music and fashion (still posing, hooked on devices, drugged to calm the eyes). Atwood was familiar with such inflexibility of women in art, or their use for it, and therefore made her own exhibit.

Space: Part I

Space: the three feet between their sunken back in line and your purse (controlled by stickers glued to the pavement and an awkward placement of your hands); the lack-there-of between a shared hug (how we create an allowance for the possibility of a greeting); an interval (the bell on a microwave, the minutes between contractions); the cycles of sleep (how religion was formed from hours of REM); a uterus (childbirth, cysts, IUDs’); the gap between breaths, cells, neurons, eyebrows.

Briefly, I want you, the reader, to remove yourself from any understanding that you are about to read a poem (and any notion that it may be life changing). Rid yourself of excitement, pride, humility, or historical insight you may feel is relevant to the female body. Now, this intangibility of your intelligence should be caressed — held with enough care that dislocation from the physical body is nurturing, yet necessary.

Here, I urge you simply, to consume.

“The woman in the spiked device

that locks around the waist and between

the legs, which holds in it like a tea strainer

is Exhibit A“

We must start with ‘The’, whose practical use in the sentence must provide a body, a root, for the further construction of a ‘woman’. Yet, Atwood extends past simple grammatical structures to dictate a tone of culpability, where name is unknown, and whose consciousness holds no weight in her description. The ‘woman’ is dismissed – nameless, muted, and withheld. By the first sentence alone, Atwood introduces the present, systemic, pornographic reality of women (who endure sexual slavery, prostitution, brutish desires and ferocious kinks). She is silenced, and more importantly, spoken for.

Even further, the frequent sexual strangulation present in pornography and sexual encounters, is leaving women with irreparable brain damage. Therefore, suggestions of ‘the woman’ being implicated as ‘brain dead’ are probable, and often passively initiated when a ‘spiked device’ strains upon the neck and legs. It is then, that the omniscient voice must dictate her despair.

What are we to then make of ‘Exhibit A?’ Are the readers meant to watch, loosely, abhorrently, decisively like one does in an art exhibit? (Never too closely, or even somewhat thoughtfully, limited to opening hours and release dates, constrained by the attention span of the viewers). Is it possible Atwood is referring to an article, doused in symmetrical red circles and frilly skirts as the women try to cover their face? Do we place the symbolism past the women to inspect her constraints, (i.e the collar, the sunken waist, the immobility of mouth and body) and leave the connotations of ‘Exhibit A’ to schoolboys’ magazine as they move the image side to side.

By the end of the first stanza, the removal of the subject is dualistic. Atwood respects the privacy of ‘the woman’ enough to soften her features, deconstructing the hard contours of breasts or a demeanour that must be conquered, while being unable to free her body from the sexual, sociological constraints – that which ‘holds [here] like a tea strainer’. A tool, designed to grasp and clench; while also actively releasing parts of itself; the dilution of the women is uncanny to modern, female autonomy.

What pleasures have I given away?

Space: Part II

“The woman in black with a net window

to see through and a four-inch

wooden peg jammed up

between her legs, so she can’t be raped

is Exhibit B“

Let us assume that Exhibit B is a photograph, which was displayed on National Geographic for the features of her face (how the world could not fathom such beauty enduring starvation, or genocide, maybe sexual abuse, and modern slavery). Let us hide the wooden peg, claim that the object was in the way of the shot, (a mental disturbance at best for the viewer) and rather focus on how the pattern of the net reflecting amongst her skin. Please do not entertain the background (the refugee camp, the perished mountains and dry soil, those rushing toward flour or the individual surrounded by bottles) rather focus on the eyes.

Who is violent, then?

—

Exhibit B builds upon the sexual strangulation of ‘the women’ in ‘devices’, while precisely eliminating her personal liberation of sexual security. The viewer must walk between the exhibits, aware of the struggle the soles of their feet encounter with the wet, marble floor to the persecution of ‘the women’s’ skin (& the unforgotten space of flesh between her legs), which to them, is all movement anyway.

Insertion is not dictated, nor coerced, it is ‘jammed’, pummelled, immobilized within her uterus. The violation is personal, yes, but the removal of space between her legs furthers the offence that she must lose in ones translation of all we are meant to sacrifice.

There was a window, (Atwood recalls), which is pliant for the man. ‘The woman’ is now a dominion, conquerable and contagious in here lack of exploitation. He is goverend by assumption, and therefore, once capable of interfence, his depravity of his violence will surpass the insertion of the wooden peg.

—

What is Exhibit B?

a) The women of Tigray, who after being forcefully raped, succumbing to the pain of nails, screws, plastic rubbish, sand, gravel, and letters jammed into their uterus.

b) Rape being a tactic of war and interastate conflicts in Sudan, by the RSF (Rapid Support Forces) which forced women into sexual enslavement, gangrape, sexual assualt against children, and enacting violence which displaced women and their children in the Dafur region.

c) The men and women in the Abu Ghraib prision in Iraq, that faced psychological torture, sexual humiliation, rape, confinement, and electrical shocks which were produced by “enhanced interrogation techniques” and what we know today as “The Hooded Man”.

d) Women, boys, girls, dogs, and animals in Palestine, Ukraine, Sudan, Congo, Vietnam, Afghantistan, Iraq, Ethipia, Mali, Nigeria, Somalia, Syria, Bosnia & Herzegovina (…) who become paramount staistics in reports a decade later, yet have succumbed to their injuries years prior.

e) Annihilation.

—

16.10.25

It was Denial in my throat. All of this.

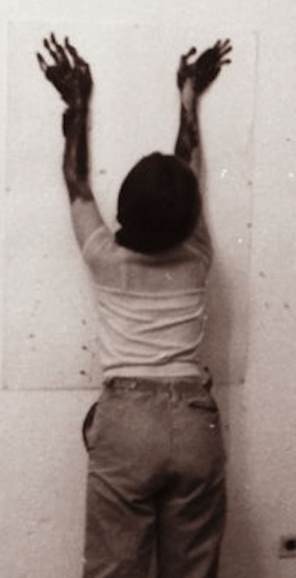

Tania Bruguera, Title: Tribute to Ana Mendieta (1985)

I was a petulant child, smothered by my own two hands — hands that were recognized, and therefore clenched.

There was little articulation amongst the imposing stature of the self, maybe it was the balancing part I struggled amongst confrontation. This ‘self’ must be considerate enough to bruise it once in a while, alongside proving the subtlety of the act alone.

Much of these days, intention is of that same false decree we hang religion from. Space (a tribute to oxymorons) must be weighed, sifted, and if appeased, saturated in front of ones mirror suitable for child-like identification. Our eyes no longer belong to the face of our mother, neither will these ‘petulant hands’, and what do I make of my righteous ability?

I have already learned how to breath.

A manuscript for greed, the breath is. Delicate and horrifyingly immeshed with a voice for death.

What else have I known?