Histories of Violence, Term 5

Key words: Anthropocene, Climate Change, Environment, Violence, Ecocriticism

Lewis and Maslin, a pair of Professors in Geology at UCL, present a paper in MacMillian as ‘Defining the Anthropocene1’ aimed at consolidating the ‘possible Anthropocene-specific’ dates, alongside ‘evidence-based decisions’ which would elucidate the consequence of this Anthropocene Epoch. A scientific and social discourse barely half a century old, the ‘Anthropocene’ Era is reliant on the deconstruction and processing power of humanity to become a primary agent of environment change, often coined Climate Change. For further precision, the introduction of the Anthropocene by the pair above, define the term within its critical tensions:

The magnitude, variety and longevity of human-induced changes, including land surface transformation and changing the composition of the atmosphere, has led to the suggestion that we should refer to the present, not as within the Holocene Epoch (as it is currently referred to), but instead as within the Anthropocene Epoch2.

Utilizing evidence-based papers and scientific diagrams, I aim to position ecological violence enacted by individuals as superior to human-on-human violence by exploring industrial pollution of Roman antiquity and the occupation of military infrastructure which posits the natural world as incorporeal.

Industrial Pollution

Humanity has been consistent in exploiting industrial pollutants, namely carbon emission and sulphur compounds. By 400 BC, Hippocrates published, ‘On Airs, Waters, and Places’ which explored the critical role of an individual (and later collective) interacting with nature. The introduction offered a candid argument of the environment, space, and human interaction: “There was a rational element, which relied upon accurate observation and accumulated experience. This rationalism concluded that disease, and health depended on environment3.” By Hippocrates argument, the individual must surpass a co-dependent relation to the outright reliance onto the environment for overall survival. Correspondingly, the naturalist and naval commander of the early Roman Empire, Pliny the Elder, dedicated pieces to the ongoing mobilization and further urbanization of the Roman Empire. A mirror of Hippocrates four centuries later, the scientist writes, “We taint the rivers and the elements of natures, and the air itself, which is the main support of life, we turn into a medium for the destruction of life4.”

Susanne Knittel5, within the field of Memory Studies examines a ‘forgotten’ approach to environmental violence, one that does not pose the socio-cultural field as its primary application: “Often, the way ecological violence is framed as violence relies on repertoires, forms and conventions for representing and commemorating genocides and other acts of large-scale violence against humans… [we should explore] the turn towards the environment and the non-human6.” Knittel’s implication of broaching the incorporeal, that which is ‘non-human’, posits the metaphysical hierarchy, currently recognized as the Anthropocene7. Applying Knittel’s proposal to the groundwork of Industrial Pollution in the Roman Empire, we can begin to address the lineage of ecological violence, beginning with lead measurements in Greenland Ice.

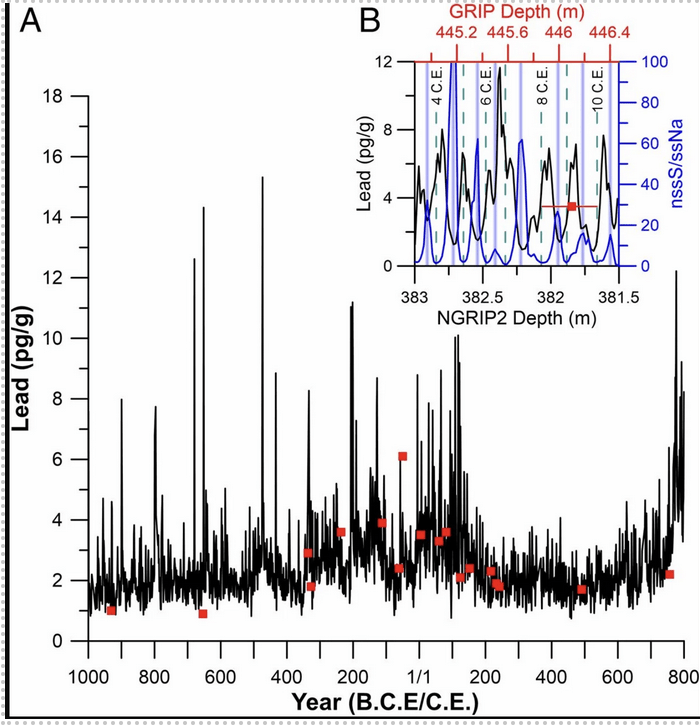

In 2018, the multidisciplinary scientific journal PNAS8, delivered a research article within Environmental Sciences, known as, ‘Lead Pollution Recorded in Greenland ice Indicates European Emissions Tracked Plagues, Wars, and Imperial Expansion during Antiquity’, which provided evidence on Roman industrial pollution peaking at the start of its emerging empire. Referencing Figure 1, the chart provides data of fluctuating lead measurements in relation to critical centuries of human development, which is contextualized by the articles abstract:

Here we show, using precisely data records of estimated lead emissions between 1100 BCE and 800 CE derived from sub annually resolved measurements in Greenland ice and detailed atmospheric transport modelling, that annual European lead emissions closely varied with historical events, including imperial expansions, wars, and major plagues9.

Figure 1. Lead measurements in Greenland Ice derived from PNAS article.

Environmental exploitation in the Roman Empire lacked any legal mediation or government interference unless the natural resource was guarded for ‘indiscriminate exploitation10.’ Notably, the persistent exploitation of ‘high temperature smelting’, large scale extraction of conquered lands and valuable elements, deforestation to combat rapid expansion, and industrial-scale operations for mining for economic profit11, produced enough emissions to penetrate the integrity of the soil and land from 500 BCE. Moreover, the biological and microscopic structures of the ice utilized for this data collection showed immense morphological changed nearly two millennium later.

Section II: Current Industrial Pollution

Many of the present phenomena, field of studies, or terminology fall under Waring, Wood and Szathmarys’ procedure of ‘Group-level Environmental Management Traits12’. Precisely, larger groups will encounter more challenges to manage their environment as they lack consistent evolutionary qualities or solutions to the developing involutions (e.g extinct species). Correspondingly, we are unable to manage the scale of social organization to readjust, convene, or faithfully deconstruct previous systems of belief.

Macroecology, a subfield in ecological studies, focuses on ‘large-scale ecological patterns across broad spatial and temporal scales,’ and is only a present-day distinction. It was a side-effect without the precaution of mobility, in which, the development of a new ecological system was necessary and could not be removed without further dislocation from the original objective. Therefore, the structures of biological and environmental distinctions must be expanded to address, study, or report on the rapid shift in our present climate conditions.

Moreover, to establish violence in the context of industrial pollution, we must refer to Serene Jones explication of the ‘traumatized physical environment’- that which must witness the ‘integrity of the creation [become] violated13’. The ‘violation’ is eventually dualistic, as the physical degradation of plants, landscapes, and synchronic climates correspond to the conceptual, biological, and evolutionary framework we have once prescribed upon nature. This ‘twofold approach’ must present a concurrent discourse of the existing conditions of nature and all that is absent to consider the future. Correspondingly, the condition of the environment will become integral to daily interaction, allowing for the destabilization of an anthropogenic perspective, as human-on-human action becomes secondary to the foundation of landscape, matter and the self-regulating processes of the Earth.

Turning to Fig. 2., The University of Leeds produced linear graphs depicting the quality of air pollution between The United Kingdom and Pakistan, drawing upon the a ‘global disparity’ amongst pollutants. While the contrast of colours may produce a positive or negative attributes, the diversity of shades becomes a concerning ‘cocktail of pollutants14’. The agriculture, cars, forest fires, burning of oil, vehicle exhaust, power plants and the fossil fuel industry united as a primary cause to a degrading ozone layer, acid rain, bleached coral reefs, scorched landscapes, and a lack of biodiversity within plants. A rather careless violence stuck in a cycle too repair itself.

Fig 2. The United Kingdom, Global Air Quality Trends15

Fig. 2, Global Air Quality Trends16

Moreover, if we are to return to Hippocrates, the presence of dense air and floating sulphur pollutants is a familiar topic. Referencing his notable texts, On ‘Airs, Waters and Places’, the naturalist writes, “They are likely to have deep, hoarse voices, because of the atmosphere, since it is usually impure and unhealthy in such places17.” The individual’s innate reliance on oxygen produced by a stable, homeostatic body, will suffer a similar violation as the integrity of the body is compromised. So, if the co-dependency of humanity onto the expansive, biological function of the Earth, reduces the anthropocentric measures to a more equal baseline of existence between nature and humans, the violence upon the environment will be held to the severity, repercussions and justice that humans have awarded themselves.

Military Infrastructure

Roman Antiquity

[…] argued that the emergence of modern bureaucratic, territorialized and centralized nation-states — marked by the monopolization of the means of violence […] — was in large part the result of protracted wars and highly expensive military campaigns, a process of co-evolution whereby ‘war made the state and state made the war18’.

Roman, military grounds were littered with dead bodies. Their armour was weaponized, buried, or reused for the solider next in line. Deforestation become a building block for invasions, providing enough resources for fuel, materials for weapons, and the space for military sites. Yet, how was military infrastructure displayed in an active war? Josephus, Jewish War, presents the siege of Jotapata as the Roman army sought the Jewish stronghold for further power in their campaign to Galilee. As the campaign makes way, the distraction of military weapons and an erected stone wall is as much a Roman display of power as it is a forceful overtaking of integral landscape:

Vespasian now brought up his artillery engines — 160 in all — and set them in a semi-circle with order to fire on the defenders on the wall. In one concerted barrage the catapults sent their spears whistling through the air, the stone-throwers hurled hundredweight rocks, and both flaming and regular arrows flew in a hail19.

Eventually, the earth will begin to scream of thirst, the charred dirt will be forced to recover, the cement left behind from the battering ram will stand still as a trophy depicting their conquer. The city will continue, with or without the inhabitants, conquerors, or those in-between, but the landscape must reclaim a buried ecosystem once more.

Section II: The Present

[…] where I, for a fraction of time, caused a security alert, because I violated this order by standing on a scrap of grass, next to a public highway, looking through a fence20.

This ‘scrap of grass’ — a space designed to hold up the fence, the shoes of her body, the cement that is to guide aircrafts, bustling bases, and artillery weapons is barely a register. The purpose has changed, unbeknownst to the grass covered in gravel or the roots pulled for concrete bases, the land lacks recognition. Nature became the first casualty, with the title of victim but lacking in the finality of justice. Thus, they are just a victim.

Fig. 3. Burning of Oil Wells in Kuwait during The Gulf War. Noted to be ‘one of the worse environmental disasters’ in recent history21.

Returning to the Anthropocene, the self-awareness of humankind becomes imperative to the assumptions one must accept for central power. An awareness catering to conditions, that of:

[…] continental trade and transport networks, eradication policies for nuisance species and diseases, agricultural pollution fines, genetic modification, anti-extinction policies and the emergence of global environmental law22.

While armed forces sustained Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD):

[..] from uranium mining and milling; through transport of ‘yellowcake’, MOX and other nuclear materials; fabrication of fuel rods; reprocessing and fast-breeder reactors; and the problems of storage of nuclear waste over millennia23.

Unsurprisingly, Nature will lack the corporeal rights, or rather the right to co-exist fairly, within a centrist collective. Even further, the environmental laws, annual summit meetings, prosecution by fines or trespassing warnings are in favour of the individual, not of the planet. They become exercises of free will, faux determinism, or ill-informed manuscripts delivered with enough enthusiasm to think moral implications are censored. We will continue to address future generations in decorated speeches, before questioning the soil degradation in Sudan. Reports of, “50 nuclear warheads and 11 nuclear reactors littering the ocean floor24” will be cleared an ‘accident’ yet the responsibility of the ocean to absorb the force of a nuclear weapon, must be rationalized as a the only ‘right’ Nature can afford.

Fig 3. is a makeshift military infrastructure. An active battlefield, with no soldiers as enemies, but rather the land as their final target. While the burning of oil wells in Kuwait were documented as a military tactic, or an economic loss for the country, the campground, uniforms, artillery shells, surveillance helicopters, and the bodies, traumatized that land. The burning fuel was violent, the weakening ground was silenced, and the smoke-filled air traumatized the natural, surrounding life. It would take over eleven months for the last oil well to be capped and the miles of ‘fire trenches25’ would be discovered.

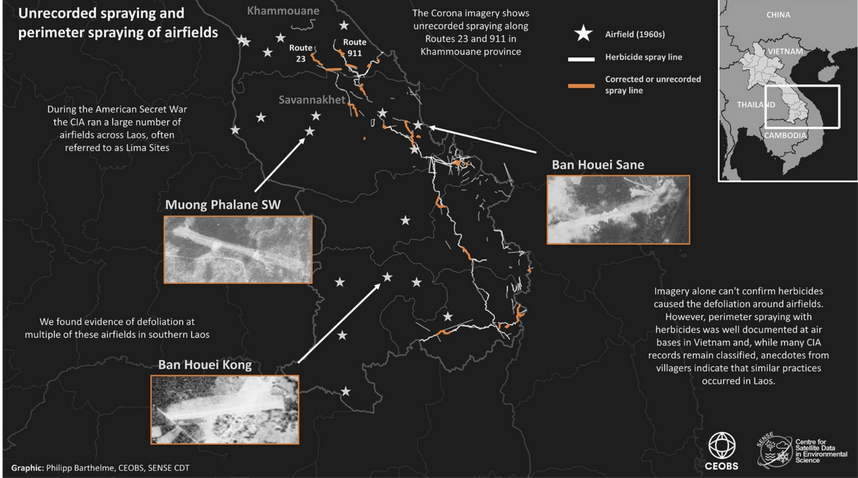

Fig 4. Unrecorded spraying of Agent Orange in Vietnam War26.

Lastly, there are a few human disasters to touch upon. Captured in Fig. 4, the use of Agent Orange in the Vietnam War became a hidden ecological disaster, as released FBI files lack the extensive records of using chemical warfare. As the black-and-white photographs display, the thick, scar-like line amongst the tree is defoliation. A common tactic within war to uncover food, shelter and aid harvesting of the opposition. The chemical agent utilized biologically alters the structures and / or compounds of the plant, forcing them to de-shed, often permanently. The land cannot recover, and the herbicide will flourish in the soil of next year’s harvest. Put simply by Pearson, “the militarization of landscape is rarely complete or final27.”

Conclusion

My aim within this paper balanced loosely between a personal, corporeal discernment and sympathies toward the incorporeal. What rights, as an individual, have I willingly taken from the environment to further this violation? Could we, as a collective, repair the tension, brutality, and suffering we have posited to be correct, moral and justified? Either way, our violence is noticeable. It is then, imperative to start on the contrary to modern thought, to focus on the corporeality, the body of the environment, as a necessary right to life.

Bibliography:

Barthleme, Phillip. 2024. ‘New Data on Agent Orange Use during the US’s Secret War in Laos – CEOBS’, CEOBS <https://ceobs.org/new-data-on-agent-orange-use-during-the-uss-secret-war-in-laos/#6> [accessed 2 December 2025]

Bostock, John, and Henry Riley. 2018. ‘The Project Gutenberg EBook of the Natural History of Pliny, Vol I., by Pliny the Elder.’, Gutenberg.org <https://www.gutenberg.org/files/57493/57493-h/57493-h.htm>

Hay-Edie, David. 1991. THE MILITARY’S IMPACT on the ENVIRONMENT: A NEGLECTED ASPECT of the SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT DEBATE a Briefing Paper for States and Non-Governmental Organisations (Sebastian) <https://www.ipb.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/briefing-paper.pdf> [accessed 1 November 2025]

Jones, W.H.S , and Hippocrates. 2023. ‘On Airs, Waters, and Places [Attributed to Hippocrates (C. 460 – C. 370 B.C.)] : Hippocrates : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive’, Internet Archive <https://archive.org/details/hippocrates-airs-waters-places-l-147/page/XIII/mode/2up>

Kersten, Jens. 2017. ‘Who Needs Rights of Nature?’, RCC Perspectives: 9–14 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268370>

Knittel, Susanne C. 2023. ‘Ecologies of Violence: Cultural Memory (Studies) and the Genocide–Ecocide Nexus’, Memory Studies, 16.6 (SAGE Publishing): 1563–78 <https://doi.org/10.1177/17506980231202747>

Leeds, University of. 2024. ‘New Images Reveal Global Air Quality Trends | University of Leeds’, Leeds.ac.uk <https://www.leeds.ac.uk/news-environment/news/article/5635/new-images-reveal-global-air-quality-trends>

Lewis, Simon, and Mark Maslin. 2015. ‘(PDF) Defining the Anthropocene’, ResearchGate <https://www.researchgate.net/publication/273467448_Defining_the_Anthropocene>

McConnell, Joseph R., Andrew I. Wilson, Andreas Stohl, Monica M. Arienzo, Nathan J. Chellman, and others. 2018. ‘Lead Pollution Recorded in Greenland Ice Indicates European Emissions Tracked Plagues, Wars, and Imperial Expansion during Antiquity’, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115.22: 5726–31 <https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1721818115>

McSorley, Kevin. 2014. ‘Towards an Embodied Sociology of War’, The Sociological Review, 62.2_suppl: 107–28 <https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954x.12194>

Pearson, Chris, Peter A Coates, and Tim Cole. 2010. Militarized Landscapes : From Gettysburg to Salisbury Plain (London ; New York: Continuum)

Salgado, Sebastiao. 2016. ‘When the Oil Fields Burned’, The New York Times <https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2016/04/08/sunday-review/exposures-kuwait-salgado.html>

Serene Jones. 2009. Trauma and Grace : Theology in a Ruptured World (Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox)

Waring, Timothy M, Zachary T Wood, and Eörs Szathmáry. 2023. ‘Characteristic Processes of Human Evolution Caused the Anthropocene and May Obstruct Its Global Solutions’, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 379.1893 (Royal Society) <https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2022.0259>

Whiston, William. 1737. ‘Josephus: Of the War, Book III’, Penelope.uchicago.edu <https://penelope.uchicago.edu/josephus/war-3.html>

Woodward, Rachel. 2004. Military Geographies (Malden, Ma: Blackwell Pub)

Zvereva, Elena L, Eija Toivonen, and Mikhail V Kozlov. 2008. ‘Changes in Species Richness of Vascular Plants under the Impact of Air Pollution: A Global Perspective’, Global Ecology and Biogeography, 17.3 (Wiley): 305–19 <https://doi.org/10.2307/30137862>