Grade: Upper Second Class, Trauma and Literature, Term 3

*This paper has been altered since the grade has been received, to formally capture the feedback given. Please note the paper was also written within the time frame of September-December of 2024, and therefore the statistics, pictures, and comments could reflect incorrect data. In this instance, it will be necessary to return to present numbers, news articles, and first-hand sources to better understand the genocide in Palestine. Here are a few resources to incite your research:

https://www.aljazeera.com/tag/israel-palestine-conflict/

“It is hostile in that you’re trying to make somebody see something the way you see it, trying to impose your idea, your picture[1].”

Joan Didion, The Paris Review (1978)

“The vast photographic catalogue of misery and injustice throughout the world has given everyone a certain familiarity with atrocity, making the horrible seem more ordinary — making it appear familiar, remote, inevitable[2]” Sontag’s depiction of ‘The ordinary’ situated to ‘the misery’ and ‘the injustice’ infiltrates photographs, capturing the declaration of life, of the Palestinian life, motivated by the zoom and the number of frames captured. It is then, as the blood marks the face, the smoke fills the lungs, and the bodies are immersed into rubble, do the the photographer’s intention clarify the fatal mark of perception — that of genocide. Notably removed from political and global refuge, the Palestinian voice is to become ostracized, devalued, constructed, and forcefully held in the fingertips gliding upon a screen, manipulating the once still photograph to amplify the face amongst rubble. In these instances, can the testimony of the survivor remain the same or does the influence of a collective social media voice, develop a disingenuous and unreliable narration from western publication of Palestinian genocide? Even further, Dori Laub’s trauma theory within testimony, incites question on an inability to perform the necessary responsibilities of the listeners (to ingest, respond, and empathize) whose further interpretation is situated amongst social media post. Critics have frequently determined the Palestine-Israel conflict to be strictly political, formed through peace agreements and government funding; however, I argue that the genocide of Palestinians should be expanded through an analysis of a formed, precarious voice integrated within social media, and to re-examine how the testimony of the witness is formed through modern applications of a virtual trauma to better understand the impact of a voice in a public, global sphere.

Theory and Trauma

Titled, “Two: Bearing Witness,” Dori Laub presents their theoretical relationship between the victim, the owner of a testimony, and the listener, that who is untouched by the experience yet a “co-owner of the [victims] traumatic event.[3]” Particularly, this act of witnessing the traumatic event, characteristic of the victim’s testimony, is reflected within a technological role — a liminal, global, transitional entity that must, by its nature, connect two parties, unanimously and unpremeditated within the expansive audience. The localization of the Palestinian voice, is stringent upon exposure, repetition, a functional screen, and heighted controls of volume to persuade a genocidal replication fit for empathic response. “The absence of an empathic listener, or more radically, the absence of an addressable other, an other who can hear the anguish of one’s memories and thus affirm and recognize their realness, annihilates the story,[4]”. Therefore, If the listener can scroll, mute, cover the screen or unfollow critical photographers, can a testimony be expressed? Is the direct voice of the listener consistently active, even without physical displacement of their body, their voice, and rather enmeshed in a virtual performativity, unable to consecutively respond back? In other words, can “reciprocal identification[5]” be achieved, if the testimony cannot be shared within a physical, or even viable space? And if the voice can be heard, shared, returned, does it matter if the cry of the survivor is deemed precarious, inequal, an ‘Other’?

Judith Butler refines ‘frame’ in her piece, Frames of War, as a “construct[ion] around one’s deed such that one’s guilty status becomes the viewer’s inevitable conclusion,[6]” yet my aim is to expand upon her objective by incorporating the conclusion of a ‘guilty status’ through the modern lens of social media. Interestingly, modernity developed a physical tangibility of Butler’s theocraticals, as the mobile phone envelops the screams, deaths, prayers, and limbs of Palestinians within a five-inch frame, alongside the ability to turn the illuminated screen into an eventual ‘gaping, vertiginous black hole,[7]” each evening. On my own terms, I will be developing the ‘precarious voice’ as an extension of Butler’s theory of precariousness, an ideal she defines as, “… one’s life is always in some sense in the hands of the other[8]” and more generally, “…attend[ing] to the suffering of others… [and] which frames permit for the representability of the human and which do not.[9]” Attributing to my theory on the precarious voice, is Mladen Dolar’s politicized voice, that must acknowledge the voice of the ‘other,’ addressed as “…the topology of extimacy, the stimuleous inclusion/exclusion, which retains the excluded to its core.[10]” Namely, the precarious [Palestinian] voice must be excluded, politicized, unequal by westernization, and exist in a framework of suffering where ‘inevitable conclusion’ captures their voice as distant, fallible, or racially inequal. The Palestinian genesis, which is their historical testimony, is consequentially limitless, fluid, and malleable by social and technological standards, deconstructed by news outlets, censored images and words, and the inability to respond while experiencing genocide. Therefore, the forced docility of Palestinian voice must surrender to the loud, expansive, fixed voice of global organizations and colonizing governments — it once more if forced to remain a constructed opinion of circumstance, a play on numbers, or a target for international powers.

Social Media as a Persona for Trauma

Scrolling, reposting, commenting, liking, sharing, donating, until the photograph of the hidden body or agonizing screams, assumes a pertinent role in articles, newspapers, talk shows, Instagram posts and Facebook arguments — it becomes controversial. The black void which must cover the despair of language, physical pain, death tolls and bombs dropped do not expect a response, it is once more a liminal, metaphysical ground capable of exposure, yet lacking the stimulation of conversation. Therefore, the listener must participate, muted or within a delayed reception, grasping at opinions from the voices of the public — dichotic, integral and “[…] crucial [to] social function.” The performance of the victim, the Palestinian confined to 8 GB of storage, must intently direct a pathos, suitable enough to contain the movement of hurried fingers, yet with enough conviction to press upon links, petitions, news articles, and GoFundMe’s. The listener must bear witness to the genocide, the gruesome images, the littered bodies, the starving children, with enough maintenance to perform dualistic procedures of social media, (scrolling, liking, sharing) yet build a steady voice for the victim, a intertextual testimony capable to withstand politicization, social alienation and economic retaliation. The owner of the testimony is not guaranteed a response, neither is the co-owner, leaving the ostracized voice to rely on civic duty and fewer bombs.

Drawing attention to Figure 1, the screenshot presents a grid of nine images which appear on the ‘For You’ page of Instagram when the word ‘Palestine’ is searched. Referring to boxes 7 and 8, pathea is artistically utilized, through red ink on ‘24’ and ‘Exterminated’, while assembling an urgency toward the present starvation and genocide. Rather than the common usage of photographs to unconsciously posit the Palestinian body under scrutiny and destruction, the declaration through literary means evolves a testimony constructed on facts and full stops. Determined, rather than filled with plea, the listener has taken the victim’s testimony (i.e photographs, videos, news articles) and transferred the ostracized voice into a statement, rather than a bargain. A western response, catering to rapid attention spans and a noticeable lack of violent images – the precarity of the Palestinian voice must hold enough censorship to allow the global co-owner to perform an assembly line of demands. It must be noted, within this first examples, that the exacerbation of Palestinian voices are forced to exist within exclusion, as the ‘Other’ through social and political denotions, therefore forcing the intertextual testimony of the Listener to succumb to social procedures of a powerless voice — the emphasis on panthea is then necessary within these instances. The “…means of (re)producing a body politic[11]” of inequal expectations, that the voice of the other can only be heard through recognizable conditions which produce death, suffering, and an inability to retaliate, condition social conventions of what is right to mourn in Western media.

Moreover, the deliberate language spreads to box 1 to utilize a platform where their dominant voice suppresses identical vocalizations by the use of requirements – you are either “Pro-Palestine or pro-genocide. There is no in between[12].” Precisely, through Allen Meek’s observations, they are forming “trauma narrative[s] constructed by public figures, media professionals, and artists to provide sites for identification[13]” Eventually, these sites strictly shape the space for voice, to conviction and expectation, toward the Palestinian suffering. Boxes four and five demonstrate the necessary persuasive language shaped by its precarious status: “One day, we will rejoice on the beaches of Gaza and celebrate a free Palestine[14]” and “Palestine will be free & Gaza will be rebuilt[15]”. A fixed voice of hope, its utterance can only incite inspiration, hope, and a necessary future, uncritical toward the genocide, but rather focused on the ability to continue the Palestinian voice.

Allen Meek’s examination of ‘cultural trauma narratives’ in his work, “Trauma in the Digital Age,” expounds upon collective trauma which suspends “the media image, like a traumatic memory, […] as the literal trace of an event: always dislocated in time and space yet experienced with a powerful sense of immediacy and involvement10.” In other words, trauma forms a collective voice and develops into a site of personal identification through photographs, articles, bolden headlines, until Palestine is suspended, rather dislocated in its present suffering and precarious voice, lost to the many countries attempting at amplifying their own testimony. Referring to Figure 2, the screenshot captures eight different narratives from countries like Chile, Australia, Lebanon, the UK, and the US, as their own social body is “recorded and disseminated,[16]” published for the correlation between personal violence and Palestine. Is it possible that the consistent exposure to traumatic images and human suffering initiated a collective narrative that has partially traumatized societies, due to an inability to fulfill Laub’s position of the listener within the survivor’s testimony? As most of this essay is formulated through inquiry, I will briefly return to Butler and Sontag to frame the possibility of such questions. In, On Photography, Susan Sontag returns to a past as she gazes upon graphic postcards:

“When I looked at those photographs, something broke. Some limit had been reached, and not only that of horror; I felt irrevocably grieved, wounded, but a part of my feelings started to tighten; something went dead, something is still crying. To suffer is one thing; another thing is living with the photographed images of suffering, which does not necessarily strengthen conscience and the ability to be compassionate. It can also corrupt them[17]”

Accordingly, trauma does not discriminate, and modernity is relentless to the morality of life; the repercussions are evident by both witnesses, that of the survivor and the listener, until their vulnerability of the skin infiltrates the emotional appeal of the Western mind. Modernity has expanded upon trauma, made it accessible, more frequent, louder, as the “agonized vocalization[18]” drowns must social construction trap the screams from the face and the displacements of the body into a lit-up screen, tucked in a back pocket. In other words, the unconscious relationship produced through social media entangles both parties, entrenched in norms and conventions, until “repeated exposure to images becomes less real.[19]” and while I doubt that apathy has severed global minds, does the repetition of screams appear duller due to their bare life? Once more, I acknowledge Butler’s framework to outline my questioning: “[…] how [do] such norms operate to produce certain subjects as “recognizable” persons and to make others decidedly more difficult to recognize.[20]” Does the precarious voice involuntarily appear less internationally, and more so through social media as repetition renders the global voice confused in its complicity? Subsequently, my field of questioning is theoretical and lacking in definitive solutions, yet the performance of social media is unequivocally fundamental to modern progression and demonstrations of a voice, and through this intertwined relationship, an analysis of global events can be attended to the immorality of human atrocity.

Palestinian Testimony

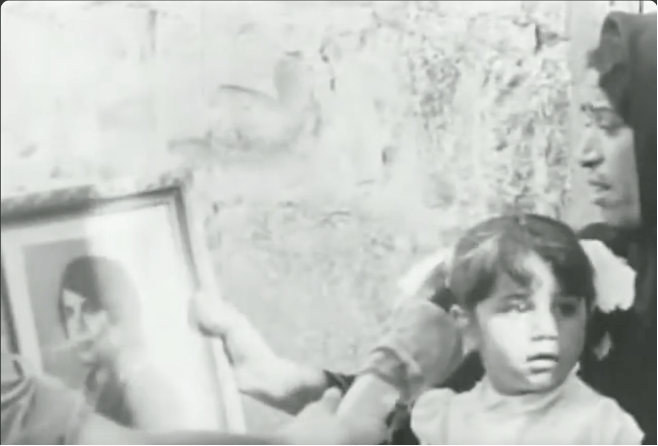

Mustafa Abu Ali’s 1974 documentary, ‘They Do Not Exist’, addresses the political landscape of Palestine, Lebanon refugee camps, guerrilla training, while also converging aesthetics to construct the beauty of the country under Israeli bombardment. After disappearing for almost a decade after the bombings of Beirut, the twenty-four minutes construct a vulnerability, one which humanizes their precarity past western construction as letters pass between child to soldier, families gather rubble from their own bedrooms, and mothers grieve their deceased children.

When formulating the Palestinian voice, the dialogue confronts their persecution and ethnic suppression, rather than encompassing their culture, beliefs, and community. Their construction of a cultural narrative must be silenced by the subjection of bombardment, suppressing expression and voices, turning them into photographs and stills. It, as in the Palestinian voice since the Nakba in 1948 became precarious. Displaced, expunged, and socially conditioned to the biological premise of ‘bare life’, their ostracized identity must rest upon the Western Saviour complex.

The headline of Figure 3 as, “There is no more Palestine… It does not EXIST” exacerbates the cultural erasure through the capitalization and denotation of ‘Exist’ to the full stop of the statement — the contrast of ‘no more’ to ‘exist’ consciously elucidates a present existence, which can only be exterminated, hindered, injured, or sequester in order to deliver the promise of the statement. Through a present reception, the use of film, categorically shies away from social media within the five decades since it release, yet the removal of orality for the replacement of falling rubble, initiated a present depiction of ecological and physical devastation amongst Palestinian land and their people. It simply appears that Abu Ali’s understand of pathea within his film, characteristically shelters the Western opinion, overshadowing the generational pain, muted despair, and consistent violence to fit into the nature of aestheticism for saviour complexes.

Giorgio Agamben extends Foucault’s biopolitics [30] to develop his theory of ‘bare life’. Akin to the precarity of voice, the Italian philosopher expresses: “[…] in the “politicization” of bare life – the metaphysical task par excellence – the humanity of living man is decided.[21]” Critically, the unconscious construction of ‘humanity’ must be postponed, hindered, and unapplicable within the application of politics — namely, a body politics of the Palestinian, unable to deconstruct the ‘Other’ or ‘Oriental’ life. Employed, the Palestinian body must integrate, join, and learn modern forms of media: TikTok, Instagram, Facebook, YouTube, etc. English must follow — plea-filled, desperate, filled to the brim with prayers to simply be heard. It is through this exchange that the endured trauma, the death and the injured, must hope that the new co-owner, the Western unprecarious voice, will deliver a testimony, careful to translate the urgency capable for movement.

Introducing Figure 4 and Figure 5, the screenshots taken from the documentary mirror the devastation in social media posts presently, yet, I find it necessary to display the Palestinian voices rupturing their own precarity, as their hope-filled monologues present a recovered future:

“I was outside during the raise I rushed to rescue my children. I found only 4. The 5th (Jahar) was not there. […] finally they found him under the rubble. It is a burning suffering for a mother. Many Palestinian mothers went through this. […] He is not the only martyr. We are all ready to sacrifice for Palestine[23]”

Surrounded by her children, Figure 5, displays a mother holding a photograph of her eldest son, killed by the bombs dropped upon the Palestinians by Israel, yet my emphasizes rest upon her last line of, “We are all ready to sacrifice for Palestine.” These sentiments are expansive and embraced all around Palestine, a national belief and passion, that has been produced on their own land, production crew, people, and voices, untouched by media outlets and news articles. The testimony of the survivor is untainted, and most notably, ends in belief even with their repeated exposure to trauma. Within this sentiment, I find it necessary to allow this essay to not only become a co-owned testimony for Palestinian voice, but a construction of the voice they have held for centuries: “Our people will never bend to oppression and killing. We are fighting for peace and justice[24]”.

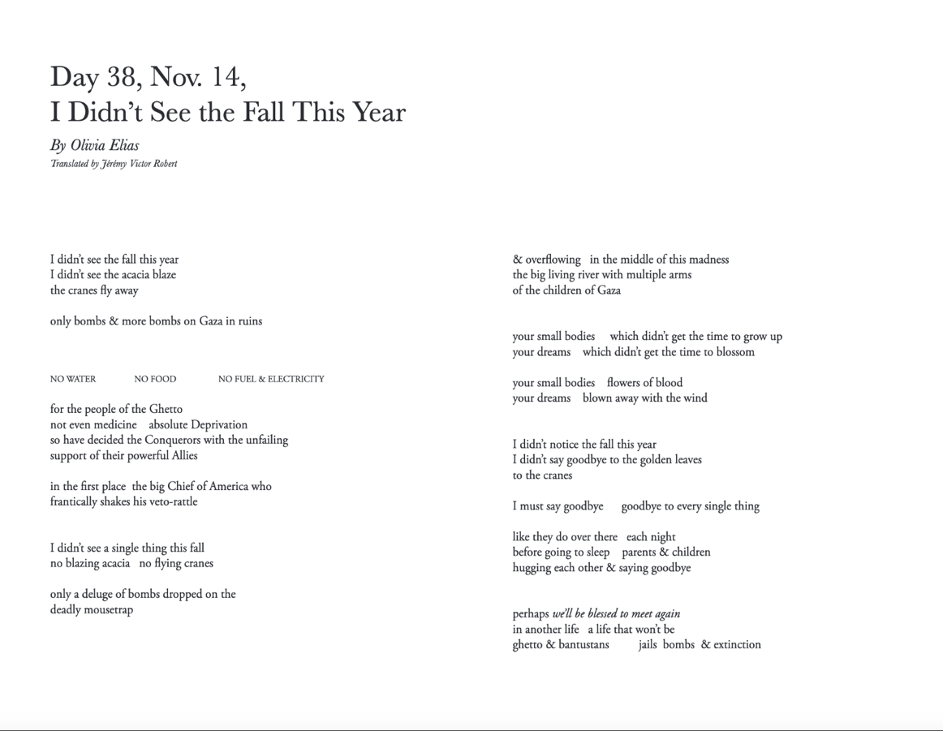

A Palestinian poet, Olivia Elias’s piece “Day 38, Nov. 14, I Didn’t See the Fall This Year” captures the continuous bombing on Gaza from October 7th and her reflection on the genocide. Referenced as Figure 6, I want to draw attention to the constructed Palestinian voice through poetic form and repetition. The spaces are intentional, physical separators that cater to the repetitive, horrifying moments of descending bombs upon the land of Palestine. “Your small bodies which didn’t get the time to grow up[25]” or “I must say goodbye goodbye to every single thing[26]” construct Elias’s precarious voice, immersed in a politicized role of addressing the immoral conditions, the uninterrupted death, the exclusion as “the Big Chief of America[27]” and the “support of their powerful Allies[28]” decimate her personal voice, when “the cranes fly away” and fall lacks a return. Agamben returns to Aristotle quoting, “[a] living animal with the additional capacity for political existence[29]” and while the philosopher is speaking upon the existence of man, precarity illustrates the dehumanization, the subjection of ‘animal’ whose existence is political, similar to Abu Ali’s documentary as the expression of fascist beliefs shape their suppression.

Overall, a lack of information is due to the limited scope of the Palestinian voice, its pertinence to social media, and its modern effects within trauma studies, leaving gaps within my claims. Several limitations present questions to be answered, as the persistent death of Palestinians and their irretrievable stories continue, yet answers may be possible in the future, especially in the field of literature, through non-fiction pieces and detailed records in the coming years. As the precarious voice was attempted, developed, and expanded, the acceptability of my remarks may be questioned, yet in the context of the political, it is necessary to address the inconsistencies and amend the rupture present in human right affairs and social issues. Overall, I attempt to argue the classified precarious voice of Palestinians, which is altered on social media not only as a witness to the events through the role of the listener, but alongside the modified testimony of the survivor as they fight to humanize themselves.

Bibliography:

Agamben, Giorgio. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life (Stanford, California Stanford University Press)

Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence (London ; New York: Verso)

Butler, Judith. 2009. Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (London; New York: Verso)

Dolar, Mladen. 2006. A Voice and Nothing More (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Mit Press, Cop)

Felman, Shoshana and Dori Laub. 1992. Testimony : Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History (New York: Routledge)

Instagram. 2020. ‘Login • Instagram’, Instagram.com <https://www.instagram.com/explore/search/keyword/?q=palestine> [accessed 20 November 2024]

Meek, Allen, ‘Trauma in the Digital Age’, in Trauma and Literature, ed. by J. Roger Kurtz, Cambridge Critical Concepts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018), pp. 167–80

Kuehl, Interviewed by Linda. 1978. ‘The Art of Fiction No. 71’, Www.theparisreview.org <https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/3439/the-art-of-fiction-no-71-joan-didion>

Arab Lit. 2023. ‘A Poem by Olivia Elias from Day 38, Nov. 14’, ARABLIT & ARABLIT QUARTERLY <https://arablit.org/2023/11/18/a-poem-by-olivia-elias-from-day-38-nov-14/>

Palestine Diary. 2010. ‘They Do Not Exist – Film by Mustafa Abu Ali’, Www.youtube.com <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2WZ_7Z6vbsg>

Sontag, Susan. 1977. On Photography (New York Picador)

The Independent. 2024. ‘Palestine’, The Independent <https://www.independent.co.uk/topic/palestine?CMP=ILC-refresh>

[1] Kuehl 1978.

[2] Sontag 2002: 21.

[3] Laub 1992: 57.

[4] Laub 1992: 68.

[5] Laub 1992: 63.

[6] Butler 2009: 8.

[7] Laub 1992: 64.

[8] Butler 2009: 14.

[9] Butler 2009: 63.

[10] Dolar 2006: 106.

[11] Meek 2018: 170.

[12] Instagram 2024

[13] Meek 2018: 168.

[14] Instagram 2024.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Meek 2018: 167.

[17] Sontag 2002: 20.

[18] Butler 2002: 133.

[19] Sontag 2002: 20.

[20] Butler 2009: 6.

[21] Agamben 1998: 8.

[23] Palestine Diary 2010: 19:57- 21:08.

[24] Palestine Diary 2010: 18:06- 18:21.

[25] Arab Lit 2023: l. 19.

[26] Arab Lit 2023: l.20.

[27] Arab Lit 2023: l. 10.

[28] Arab Lit 2023 : l.9.

[29] Agamben 1998: 7.

[30] Foucault’s biopolitics can be discovered within his work, History of Sexuality, and develops the idea as ‘a political rationality which takes the administration of life and populations as its subject: ‘to ensure, sustain, and multiply life, to put this life in order”

Figure 1: ScreenshotInstagram Feed when ‘Palestine’ is searched on the ‘For You’ page.

Figure 2: Screenshot of the main page, Al Jazeera News Feed, September 15 2024.

Figure 3: Screenshot of scene from ‘They Do Not Exist’. Youtube.

Figure 4: Still from documentary, ‘They Do Not Exist’. Youtube.

Figure 5: Still of documentary, ‘They Do Not Exist’. Youtube.

Figure 6: Olivia Elias, ‘Day 38, Nov. 14, I Didn’t See the Fall This Year’

Leave a comment