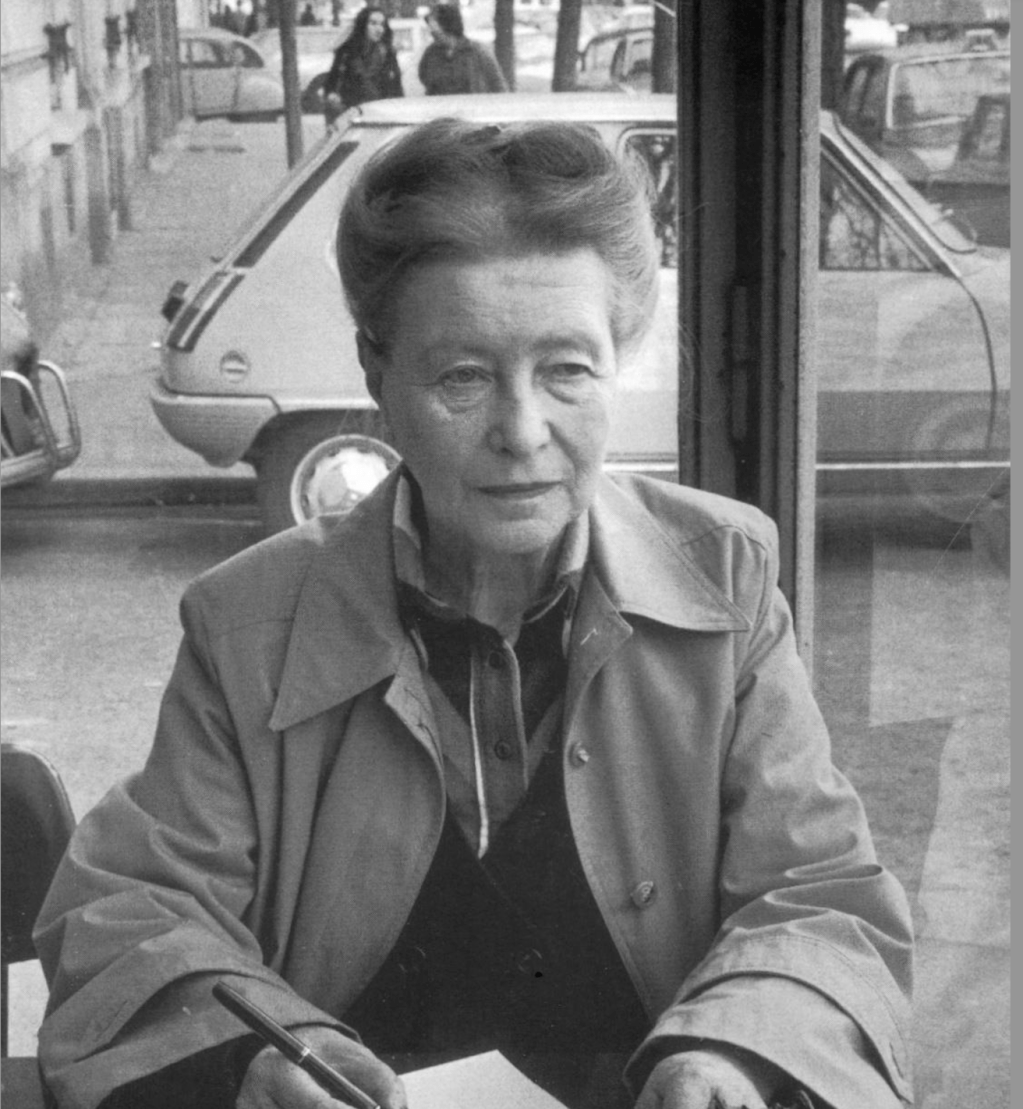

Simone De Beauvoir, an existentialist philosopher whose developed critique on feminist theory enacts a sort of ‘second- wave’ feminism, publishes The Woman Destroyed, whose sentiments and serpentine excerpts enact the lives of three women whose crisis is not a matter of age and lack of youthful-like endeavours but the inability to return to the past, whether their love is castrated by unfaithful husbands or the ‘second-shift’ of tending to their children. What becomes fascinating is each women slowly begin to blend together in relation to such issue. ‘Idiotic Vanity’ Beauvoir deems, the women’s inability to play into such notions that even men who can carry out propositions of love, who play into the term of ‘soulmate’ or anything akin to holding such high regard, are fooling themselves and only regarding their ego. Looking into all three women, Monique’s tumultuous relationship with her husband after his affair becomes a mutual acknowledgement between both, plays into her emotional state early on, outlining the dilemma each women encounters, years past their ‘prime.’

“All women think they are different; they all think there are some things that will never happen to them; and they are all wrong” (136).

The Age of Discretion

Beauvoir removing names as an identifier in conversation, leaves examinations to be marked by titles such as, ‘main character’ or rather ‘woman.’ These sections will be outlined by the term, ‘woman’ ‘mother’ or anything adjacent as means to describe the characters mentioned in the novel. Looking into The Age of Discretion, the first part of the novel builds conflicting emotions of youth, rather the lack of it, as the hands of the clocks continue their journey. The mother, now stuck in her inability to create a novel idea yet untouched by the publishing industry, begins to down spiral when her only child, a son whose intelligence and political opinion is attributed to that of his parents, begins to ‘defy’ his mothers wishes of sticking to education and teaching in favour for a political job, one marked to be for the other side. As youth becomes a heavy subject both by the mothers lack of acceptance and her husbands keen embracement of ‘old age’ conversations become tense, rather shaped on miscommunication and terse engagements. Beauvoir continues to write:

“No. At my age one has habits of mind that hamper inventiveness. And I grow more ignorant year by year” (17)

“The less I identify myself with my body the more I feel myself required to take care of it. It relies on me, and I look after it with bored conscientiousness, as I might look after a somewhat reduced, somewhat wanting old friend who needed my help” (23)

The plight of youthfulness slides among the pages, entrenching each rushed conversation, leading the way a compass might, and in doing so not only creates tension between the mother and her inability to prescribe a closer relationship to her son, but also the confusion of not understanding her husband anymore due to his ill attempt at grasping life like she. The continual regurgitation of the past is felt with the linking of clocks and watches and light turning to darkness allowing a cycle to flourish, leaving the heart stricken mother unable to move forward. The conflict continues, an incapability to align herself with the thoughts of those outside of her, leaves her shameless, often playing into the miscommunication trope all readers feign to hate.

“It was I who molded his life. Now I am watching it from outside, a remote spectator. It is the fate common to all mothers; but who has ever found comfort in saying that hers is the common fate?” (29)

“The two pictures I had, of the past André and the present André, did not coincide. There was an error somewhere” (43)

The lack of dependency by both men here, in this case emotional resemblance, causes the mother to question her role in her sons childhood, an uncomfortable possessiveness pushed in between lines as she tries to reclaim her son as her own. Every girls worst fear – a mother – in – law attached to the hip of her son, and as she loses touch with the ability to control his positions in life, her full-proof plan of comfortability collapses as her husbands arguments find home in the other side. The intimacy in sections of turmoil between each characters made me cringe and possibly awkwardly laugh through her bouts of covetousness as the pondering of emotional incest is not lost within your own mental connections, but the rawness of her grieve and inability to persist without the men in her life, gives way to some viable truth mothers rarely ingest themselves. That their youth is no longer dispensable and to require such efforts toward yourself is unjust. That the feeling of being ‘invalid’ is marked by an empty home where pots are only touched by your hands and grocery trips cover 1/3 of the fridge, and to leave such notion of women’s identity tied to her ability to reproduce and have children and when left with the loneliness of during and after, their present identity is still marked by their past. One of staring quotes wraps up her internal fight toward youthfulness, as she claims herself to be:

“I am not young: I am well preserved” (64)

To end the first section, the last points I wish to digress on are such: how much should a parent muddle into their child’s life and at what point is protectiveness or even support, overbearing and conflicting? and Simone to end this section on a note of hopefulness, a note of contentment and overall acceptance toward her situation and the conflict she felt toward her loving relationships writing, “We are together: that is our good fortune. We shall help one another to live through this last adventure, this adventure from which we shall not come back. Will that make it bearable for us? I do not know. Let us hope so. We have no choice in the matter” (85). Her ending tone of cooperation seems needed after the mother’s long digression with her fear of the future, and while some might find her words lacking with her front of simplicity and good-natured ‘approval’ of her new life, Beauvoir decision to end this act of discretion with a few minor sentences with no defining statement, no established emotion, pushes for a new kind of ‘humanness,’ one where you don’t have to understand your present, so long as your don’t fight against it to reclaim who you were in the past.

The Monologue

Beauvoir second piece, opening with the quote, “The monologue is her form of revenge,” challenges the stereotypes of grammar and the importance of comma’s, as her shortest section delves into the bitterness of a mother who loss of her daughter exhibits reoccurring moments of grief and unnerving anger as she cuts ties with her husband, and later family. Written as a vitriolic diatribe, the movement of anger is a burning vice for the grieving mother, now facing the multitude of affairs that must be acknowledged in her family. Her down-spiral consumes each word in the text, creating a confusing, questionable monologue. While those who pride themselves on their ability to succeed in grammar years ago, Beauvoir’s decision to make the monologue almost unreadable at points, where the reader must return to what the mother is trying to convey, accurately portrays the struggle woman face when caste aside in their own family, a designated role in society. While I can deliver my own monologue of destruction that patriarchy has created, Simone uses a simple forgotten voice of a mother to depict the struggles quite well. As stated above, family is a running topic in this section, the necessity to keep all of them together begins to ruin her identity as a ‘mother.’

“I want to be treated with respect I want my husband my son my home like everybody else” (96)

And her most stirring issue; her daughter:

“I should have won her back. I’d have made her into a worthwhile person. But it would have taken me time” (105)

“Sylvie died without understanding me I’ll never get over it. […] All that effort all those struggles scenes sacrifices — all in vain. My life’s work gone up in smoke” (106)

A fixation on her daughter, creates the parallel that all woman endure: the suffering and struggle the mother encountered and such a cycle impedes the growth of the daughter, hindering and discouraging her from firstly, existing. While the structure of patriarchy is not a key theme in this section, particularly, the passing of anger and/or resentment, and a need for an individuality complex stems from the mother, where her repressed anger, whether produced from that of her husband or the conflicts of society, is further exacerbated by the known suffering she is to endure in the future. While I could be looking to far into this, the relationship present between mother and daughter is established as weary, one caused for escape, and as her daughter enacts suicide, the suffering of the mother is ten-fold, sequestering her to abject loneliness, as her willingness of her husbands affair only falls to the loss of her presence in her son’s life. So as not the spoil most of the monologue, Beauvoir brings up women’s relationships in a few twisted lights in all sections of the novel, the relationships of the mother and her friends becoming a picturesque model for such interaction:

“I had spoken to her out of loyalty women have to stand by one another. Who had ever shown me any gratitude? (112)

“You mustn’t let yourself be eaten up” she tells me. But she’d be delighted to swallow me whole” (113)

Often, in fiction centred around the suffering of women where the root of such is by men, the relationships formed between women become a solidifier, a theme perhaps, where words of wisdom inscribe their conversations and vows of healing, yet Beauvoir’s rejection of this narrative, plays into the whole, ‘I am a women on my own,’ which can be inspiring in some ways, but I don’t think Simone intended this. Being a known feminist activist, this former narrative is built on pity and inability causing the correlation between ideas to fall short. With the quote,

“I was simpleminded — I thought they were capable of turning over new leaves I thought you could bring them by making them see reason” (112)

[continued] it suppresses impotence and replaces it with questions of personal reason and worth. With the position of mother in the hierarchy, she is already diminished and demanded of her value, further creating acceptance of treatment by personally demoting herself in favour of her children, a self-sacrifice if you must, yet after demanding so little of herself, she expect others to see the abandonment of herself, yet this also fails as well. Simone proceeds to characterise this mother as one who has not only lost her daughter, but now her son to a husband riddled with affairs, while also becoming detached with unsympathetic family in order to prescribe the conditions of a woman, whose lack of empathy received by others has granted her an entire thirty page monologue, riddled with forgotten commas and run-on sentences, to show how the sacrifice has evolved into anger. She has made a woman in the only way possible: neglect.

Simone ends this section with two short sentences, a win for all the grammar police out there, and its little movement on the pages provides all that is needed for women forgotten:

“You owe me this revenge, God. I insist that you grant me it” (120)

While the shortest section, this piece enacts the rage of women and the abundance of such emotion we are made to feel. The seamless integration of rejections by those who made her a mother, a daughter, an individual, creates an atmosphere of a women who can no longer prescribe to the very values that made her. Such revenge can only be acted upon in this case and lack of action only leads to the same death as her daughter: suicide.

The Woman Destroyed

Beauvoir’s final part, a needed reference to the title, carries on the varying themes mentioned in previous section, as she delves into a long standing marriage destroyed by the husband’s ever-growing affair. Simon seems enlightened by the psychology of the affair, the steady insanity and conditioned acceptance reinstated by women, drives the narrative as this mother now concerns herself with an internal struggle of moral justification and physical love. The tarnishing of self-worth transpires through her relationships starting with her husband, through her daughters, and to other outside friendships / engagements. Given the multitude of interaction and struggle, the development of many themes and statements arise on surviving grief. The primary struggle, again with the patriarchy, is the ideal that husbands are to grow weary of their wives and so him having an affair is normal, needed even to keep his peace and youth. Such quotes nuture this ideology:

“I have had exactly the kind of life I wanted — now I must deserve that privilege” (137).

“He is lying so as to ease things for me. If he eases things for me that means that he values me. In a way it would be worse if he were quite brazen” (176)

Entertaining such quotes, the sense of patriarchal interference reaks in the entirety of this section with the soothing attitude, “You are lucky he has decided to stay with you and not the other woman.” In this context, the mother’s disintegration develops into a hierarchy of self-examination to all aspects of inter-personal relationships, where the obvious start is that of her husband. As mentioned above, the psychological conditioning of acceptance turns into the questioning of love for both parties, whether he actually did love her or if she reciprocated such emotion enough. Beauvoir’s thorough depiction of regression reminds me of Sylvia Plath, The Bell Jar, in ability to transform to the mental processes of an individual that lead to questions of insanity and death. The mothers eventual progress to questioning key emotions can be noticed when Simone writes,

“I have never asked anything for myself that I did not also wish for him” (135)

“I had to make sure that a man could still find me desirable. That has been proved. And where does it get me? It has not made me any more desirable to myself” (169)

“The question is why did he love my in the first place? […] For my part I loved him when he was twenty-three — an uncertain future — difficulties. I loved him with no security; and I gave up the idea of a career for myself. Anyhow I regret nothing” (195)

While Simone does play into the guilt the husband feels for grief the mother is encountering, the shift in focus to the mother’s personal inability to cope developed no empathy over the husband’s personal afflictions. As the topics of feelings drive this side of the narrative, the range of emotion explored in this piece creates wonderful stability for the mother to be explored from such a psychological hierarchy, even if it was not intended to be so. By stripping the husbands voice, it furthers the notion of woman being able to contemplate the very same existentialistic questions. The shift is not gradual, but rather blended as the women maintain both the perspective of catering to her husband and questioning her self-worth, leaving a few minor infuriating moments as a reader. The hierarchy evolves along with her personal onslaught into the mother’s main identity: her children. Mother-daughter relationships are the foreground to each suffering woman in Beauvoir’s narrative, and in this case, the switching of roles creates complexities as both the mother and husband carry worries, yet the development of all three woman hold ground for positivity, and even empathy despite each other personality. Beauvoir depicts this as:

“Fathers never have exactly the daughters they want because they invent a notion of them that the daughters have to conform to. Mothers accept them as they are” (163)

“If I have failed with the bringing up of my daughter, my whole life has been a mere failure” (215).

“My only life has been to create happiness around me. I have not made Maurice happy. Any my daughters are not happy either. So what then? I no longer know anything. Not only do I not know what kind of person I am, but also I do not know what kind of person I ought to be” (252)

As stated in prior sections, as the mother is defined by her relation to her children, the root, the internal identification of herself does not seem to equal the recognition of motherhood, in so the woman’s capacity to provide rather than the appreciation of the role in practice. The hierarchy continues to evolve as the mother now concerns such worries with herself, as the interest of self-worth becomes a known concern toward the end of the piece. Beauvoir attaches to the emotion of contentment as means of creating a basis for how the mother is supposed to feel. She was supposed to accept her husbands affair willingly, even with a degree of happiness. She had to accept the publicity, lack of familial support, burnout from her passions, lack of self-value all for her husband to continue said affair, yet her jump to self-questioning, while months after the affair started, became the needed ending to the families story. The next section of quotes highlights growth in relation too questioning thy self while also highlighting the emotional struggle woman will encounter in daily relationships.

“I asked Isabelle whether she was happy. “I never ask myself, so I suppose the answer is yes” (140)

“In fact I am defenseless because I have never supposed I had any rights. I expect a lot of the people I love — to much, perhaps. I expect a lot, and I even as for it. But i do not know how to insist” (151)

“But I won’t, I won’t! I am forty-four; it’s top early to die — it’s unfair! I can’t live any longer. I don’t want to die” (223).

“Things have been given other names: they have not altered in any way. I have learned nothing. The past remains as obscure as ever. The future remains uncertain” (209)

The permanence of grief continues, the acknowledged struggle of self-preservation, the understanding the such relationships lived through could in theory be forgotten over time but cannot be wiped away, only shaped and twisted. Throughout the novel, the most cathartic section had to be the last remaining pages of this section, where the self-identification is raw, poignant, and severely needed. The last remaining quotes provide a basis for truth even without a concluding ending.

“‘What else do I possess?’ The heavy silence. I possess nothing other than my past” (214)

“Tragedies are all right for a while: you are concerned, you are curious, you feel good. And then it gets repetitive, it doesn’t advance, it grows dreadfully boring: it is so very boring, even for me” (239).

“I am on the threshold. There is only this door and what is watching behind it. I am afraid. And I cannot call to anyone for help. I am afraid” (254).

To end this sweetly, Simone de Beauvoir’s published text, The Woman Destroyed, can be complicit with those who are struggling with lost youth, who identify as a woman, whose grief is consuming and old enough to have a name. It is one that you process a little week later, prescribed too long, dark nights and blaring music, and you begin to understand the loss of what it means to be a woman and love dearly, closely, and too much. If you begin to question such intimate, particular moments of looking at clocks too closely, reminiscing of clothes to tight, and phone calls never placed, Beauvoir might just be the perfect medication.

Leave a comment